123 You Know Silk a G

| Silk | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

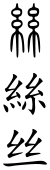

"Silk" in seal script (summit), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (lesser) Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 絲 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 丝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese proper noun | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 絹 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | シルク | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Silk is a natural poly peptide cobweb, some forms of which tin can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced past certain insect larvae to form cocoons.[one] The best-known silk is obtained from the cocoons of the larvae of the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori reared in captivity (sericulture). The shimmering appearance of silk is due to the triangular prism-similar structure of the silk fibre, which allows silk textile to refract incoming low-cal at different angles, thus producing different colors.

Silk is produced by several insects; but, more often than not, simply the silk of moth caterpillars has been used for fabric manufacturing. In that location has been some inquiry into other types of silk, which differ at the molecular level.[2] Silk is mainly produced by the larvae of insects undergoing consummate metamorphosis, but some insects, such as webspinners and raspy crickets, produce silk throughout their lives.[3] Silk production also occurs in hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and ants), silverfish, mayflies, thrips, leafhoppers, beetles, lacewings, fleas, flies, and midges.[2] Other types of arthropods produce silk, nigh notably diverse arachnids, such as spiders.

Etymology

The word silk comes from Sometime English: sioloc , from Ancient Greek: σηρικός, romanized: sērikós , "silken", ultimately from the Chinese word "sī" and other Asian sources—compare Mandarin sī "silk", Manchurian sirghe , Mongolian sirkek .[4]

History

The production of silk originated in China in the Neolithic catamenia, although it would eventually reach other places of the globe ( Yangshao culture, 4th millennium BC). Silk production remained confined to People's republic of china until the Silk Route opened at some point during the latter part of the 1st millennium BC, though China maintained its virtual monopoly over silk production for some other thousand years.

Wild silk

Rearing of wild Eri silk worm, equally seen in 7Weaves, Assam

Several kinds of wild silk, produced past caterpillars other than the mulberry silkworm, have been known and spun in People's republic of china, Southern asia, and Europe since ancient times, e.g. the production of Eri silk in Assam, India. However, the scale of production was always far smaller than for cultivated silks. There are several reasons for this: beginning, they differ from the domesticated varieties in colour and texture and are therefore less uniform; second, cocoons gathered in the wild have usually had the pupa sally from them before being discovered so the silk thread that makes up the cocoon has been torn into shorter lengths; and third, many wild cocoons are covered in a mineral layer that prevents attempts to reel from them long strands of silk.[5] Thus, the only way to obtain silk suitable for spinning into textiles in areas where commercial silks are not cultivated was by slow and labor-intensive carding.

Some natural silk structures take been used without being unwound or spun. Spider webs were used every bit a wound dressing in ancient Greece and Rome,[6] and as a base for painting from the 16th century.[seven] Caterpillar nests were pasted together to brand a fabric in the Aztec Empire.[8]

Commercial silks originate from reared silkworm pupae, which are bred to produce a white-colored silk thread with no mineral on the surface. The pupae are killed by either dipping them in humid h2o earlier the adult moths emerge or by piercing them with a needle. These factors all contribute to the power of the whole cocoon to be unravelled as 1 continuous thread, permitting a much stronger cloth to exist woven from the silk. Wild silks also tend to be more difficult to dye than silk from the cultivated silkworm.[9] [ten] A technique known as demineralizing allows the mineral layer around the cocoon of wild silk moths to exist removed,[xi] leaving simply variability in color as a barrier to creating a commercial silk industry based on wild silks in the parts of the world where wild silk moths thrive, such as in Africa and Southward America.

Prc

Silk use in fabric was first adult in ancient Communist china.[12] [thirteen] The primeval evidence for silk is the presence of the silk protein fibroin in soil samples from two tombs at the neolithic site Jiahu in Henan, which date dorsum near 8,500 years.[14] [15] The primeval surviving example of silk fabric dates from nearly 3630 BC, and was used as the wrapping for the torso of a kid at a Yangshao civilisation site in Qingtaicun near Xingyang, Henan.[12] [16]

Legend gives credit for developing silk to a Chinese empress, Leizu (Hsi-Ling-Shih, Lei-Tzu). Silks were originally reserved for the Emperors of People's republic of china for their ain utilize and gifts to others, but spread gradually through Chinese culture and trade both geographically and socially, and so to many regions of Asia. Because of its texture and lustre, silk speedily became a pop luxury textile in the many areas accessible to Chinese merchants. Silk was in great demand, and became a staple of pre-industrial international merchandise. Silk was also used as a surface for writing, especially during the Warring States catamenia (475-221 BCE). The cloth was light, information technology survived the clammy climate of the Yangtze region, captivated ink well, and provided a white background for the text.[17] In July 2007, archaeologists discovered intricately woven and dyed silk textiles in a tomb in Jiangxi province, dated to the Eastern Zhou dynasty roughly ii,500 years agone.[18] Although historians have suspected a long history of a formative textile industry in ancient China, this notice of silk textiles employing "complicated techniques" of weaving and dyeing provides straight evidence for silks dating earlier the Mawangdui-discovery and other silks dating to the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD).[xviii]

Silk is described in a chapter of the Fan Shengzhi shu from the Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD). There is a surviving calendar for silk production in an Eastern Han (25–220 Ad) document. The two other known works on silk from the Han flow are lost.[12] The first evidence of the long distance silk merchandise is the finding of silk in the pilus of an Egyptian mummy of the 21st dynasty, c.1070 BC.[xix] The silk trade reached as far as the Indian subcontinent, the Middle Due east, Europe, and Northward Africa. This merchandise was and so extensive that the major set of trade routes between Europe and Asia came to be known equally the Silk Road.

The Emperors of China strove to keep knowledge of sericulture secret to maintain the Chinese monopoly. Nonetheless, sericulture reached Korea with technological aid from People's republic of china around 200 BC,[20] the ancient Kingdom of Khotan by AD 50,[21] and India past AD 140.[22]

In the ancient era, silk from China was the most lucrative and sought-afterwards luxury item traded across the Eurasian continent,[23] and many civilizations, such as the ancient Persians, benefited economically from trade.[23]

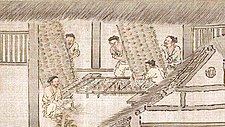

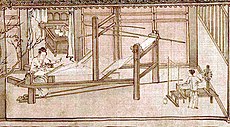

- Chinese silk making process

-

The silkworms and mulberry leaves are placed on trays.

-

Twig frames for the silkworms are prepared.

-

The cocoons are weighed.

-

The cocoons are soaked and the silk is wound on spools.

-

The silk is woven using a loom.

Northeastern Republic of india

In the northeastern state of Assam, three dissimilar types of indigenous diverseness of silk are produced, collectively called Assam silk: Muga, Eri, and Pat silk. Muga, the aureate silk, and Eri are produced by silkworms that are native just to Assam. They have been reared since ancient times like to other East and Southward-Eastward Asian countries.

India

Silk sari weaving at Kanchipuram

Silk has a long history in Republic of india. Information technology is known as Resham in eastern and north India, and Pattu in southern parts of India. Contempo archaeological discoveries in Harappa and Chanhu-daro propose that sericulture, employing wild silk threads from native silkworm species, existed in Southern asia during the time of the Indus Valley Civilisation (now in Pakistan and India) dating between 2450 BC and 2000 BC, while "hard and fast evidence" for silk product in Red china dates back to around 2570 BC.[24] [25] Shelagh Vainker, a silk expert at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, who sees evidence for silk production in China "significantly earlier" than 2500–2000 BC, suggests, "people of the Indus civilisation either harvested silkworm cocoons or traded with people who did, and that they knew a considerable amount near silk."[24]

Bharat is the 2nd largest producer of silk in the world after China. Near 97% of the raw mulberry silk comes from six Indian states, namely, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Jammu and Kashmir, Tamil Nadu, Bihar, and W Bengal.[26] North Bangalore, the upcoming site of a $twenty million "Silk Urban center" Ramanagara and Mysore, contribute to a majority of silk product in Karnataka.[27]

Antheraea assamensis, the owned species in the state of Assam, India

In Tamil Nadu, mulberry cultivation is concentrated in the Coimbatore, Erode, Bhagalpuri, Tiruppur, Salem, and Dharmapuri districts. Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, and Gobichettipalayam, Tamil Nadu, were the first locations to have automatic silk reeling units in India.[28]

Thailand

Silk is produced year-round in Thailand by two types of silkworms, the cultured Bombycidae and wild Saturniidae. Nearly product is after the rice harvest in the southern and northeastern parts of the state. Women traditionally weave silk on manus looms and laissez passer the skill on to their daughters, as weaving is considered to be a sign of maturity and eligibility for marriage. Thai silk textiles frequently employ complicated patterns in various colours and styles. Most regions of Thailand have their ain typical silks. A single thread filament is as well thin to employ on its own so women combine many threads to produce a thicker, usable fiber. They do this by hand-reeling the threads onto a wooden spindle to produce a uniform strand of raw silk. The process takes effectually 40 hours to produce a one-half kilogram of silk. Many local operations use a reeling machine for this job, but some silk threads are yet hand-reeled. The difference is that hand-reeled threads produce three grades of silk: two fine grades that are ideal for lightweight fabrics, and a thick grade for heavier textile.

The silk textile is soaked in extremely cold water and bleached before dyeing to remove the natural yellowish coloring of Thai silk yarn. To practise this, skeins of silk thread are immersed in big tubs of hydrogen peroxide. Once washed and stale, the silk is woven on a traditional hand-operated loom.[29]

Bangladesh

The Rajshahi Division of northern People's republic of bangladesh is the hub of the country's silk industry. There are three types of silk produced in the region: mulberry, endi, and tassar. Bengali silk was a major detail of international merchandise for centuries. Information technology was known as Ganges silk in medieval Europe. Bengal was the leading exporter of silk between the 16th and 19th centuries.[thirty]

Central Asia

Chinese Embassy, carrying silk and a string of silkworm cocoons, 7th century CE, Afrasiyab, Sogdia.[31]

The 7th century CE murals of Afrasiyab in Samarkand, Sogdiana, testify a Chinese Diplomatic mission carrying silk and a string of silkworm cocoons to the local Sogdian ruler.[31]

Middle E

In the Torah, a scarlet fabric item called in Hebrew "sheni tola'at" שני תולעת – literally "blood-red of the worm" – is described as beingness used in purification ceremonies, such as those following a leprosy outbreak (Leviticus 14), aslope cedar woods and hyssop (za'atar). Eminent scholar and leading medieval translator of Jewish sources and books of the Bible into Arabic, Rabbi Saadia Gaon, translates this phrase explicitly equally "scarlet silk" – חריר קרמז حرير قرمز.

In Islamic teachings, Muslim men are forbidden to wearable silk. Many religious jurists believe the reasoning behind the prohibition lies in avoiding article of clothing for men that can be considered feminine or extravagant.[32] There are disputes regarding the corporeality of silk a textile tin consist of (e.thou., whether a small decorative silk slice on a cotton wool caftan is permissible or not) for it to be lawful for men to clothing, but the dominant opinion of most Muslim scholars is that the wearing of silk by men is forbidden. Modern attire has raised a number of bug, including, for instance, the permissibility of wearing silk neckties, which are masculine articles of clothing.

Ancient Mediterranean

In the Odyssey, 19.233, when Odysseus, while pretending to exist someone else, is questioned past Penelope about her husband's clothing, he says that he wore a shirt "gleaming similar the peel of a dried onion" (varies with translations, literal translation hither)[33] which could refer to the lustrous quality of silk fabric. Aristotle wrote of Coa vestis, a wild silk textile from Kos. Sea silk from certain large sea shells was as well valued. The Roman Empire knew of and traded in silk, and Chinese silk was the about highly priced luxury good imported by them.[23] During the reign of emperor Tiberius, sumptuary laws were passed that forbade men from wearing silk garments, but these proved ineffectual.[34] The Historia Augusta mentions that the third-century emperor Elagabalus was the first Roman to vesture garments of pure silk, whereas it had been customary to clothing fabrics of silk/cotton fiber or silk/linen blends.[35] Despite the popularity of silk, the secret of silk-making merely reached Europe around AD 550, via the Byzantine Empire. Contemporary accounts state that monks working for the emperor Justinian I smuggled silkworm eggs to Constantinople from China inside hollow canes.[36] All top-quality looms and weavers were located inside the Keen Palace complex in Constantinople, and the cloth produced was used in regal robes or in affairs, every bit gifts to foreign dignitaries. The remainder was sold at very high prices.

Medieval and modern Europe

Silk satin leaf, forest sticks, and guards, c. 1890

Italy was the about important producer of silk during the Medieval historic period. The outset center to introduce silk production to Italy was the city of Catanzaro during the 11th century in the region of Calabria. The silk of Catanzaro supplied virtually all of Europe and was sold in a large market fair in the port of Reggio Calabria, to Spanish, Venetian, Genovese, and Dutch merchants. Catanzaro became the lace capital of the world with a big silkworm breeding facility that produced all the laces and linens used in the Vatican. The city was world-famous for its fine fabrication of silks, velvets, damasks, and brocades.[37]

Another notable center was the Italian metropolis-land of Lucca which largely financed itself through silk-product and silk-trading, commencement in the 12th century. Other Italian cities involved in silk production were Genoa, Venice, and Florence. The Piedmont area of Northern Italian republic became a major silk producing surface area when h2o-powered silk throwing machines were adult.[38]

The Silk Exchange in Valencia from the 15th century—where previously in 1348 also perxal (percale) was traded as some kind of silk—illustrates the power and wealth of one of the great Mediterranean mercantile cities.[39] [40]

Silk was produced in and exported from the province of Granada, Spain, especially the Alpujarras region, until the Moriscos, whose industry it was, were expelled from Granada in 1571.[41] [42]

Since the 15th century, silk production in French republic has been centered around the city of Lyon where many mechanic tools for mass product were offset introduced in the 17th century.

"La charmante rencontre", rare 18th-century embroidery in silk of Lyon (private collection)

James I attempted to establish silk product in England, purchasing and planting 100,000 mulberry trees, some on land adjacent to Hampton Court Palace, but they were of a species unsuited to the silk worms, and the attempt failed. In 1732 John Guardivaglio gear up upwards a silk throwing enterprise at Logwood manufactory in Stockport; in 1744, Burton Mill was erected in Macclesfield; and in 1753 Old Mill was congenital in Congleton.[43] These 3 towns remained the heart of the English language silk throwing industry until silk throwing was replaced by silk waste spinning. British enterprise also established silk filature in Cyprus in 1928. In England in the mid-20th century, raw silk was produced at Lullingstone Castle in Kent. Silkworms were raised and reeled under the direction of Zoe Lady Hart Dyke, later moving to Ayot St Lawrence in Hertfordshire in 1956.[44]

During Globe War II, supplies of silk for UK parachute industry were secured from the Middle East by Peter Gaddum.[45]

- Medieval and modern Europe

-

Dress made from silk

-

Bed covered with silk

-

A hundred-yr-quondam pattern of silk called "Almgrensrosen"

North America

Wild silk taken from the nests of native caterpillars was used by the Aztecs to brand containers and as paper.[49] [viii] Silkworms were introduced to Oaxaca from Kingdom of spain in the 1530s and the region profited from silk production until the early 17th century, when the king of Espana banned export to protect Spain's silk industry. Silk production for local consumption has continued until the present day, sometimes spinning wild silk.[fifty]

King James I introduced silk-growing to the British colonies in America effectually 1619, ostensibly to discourage tobacco planting. The Shakers in Kentucky adopted the practice.

Satin from Mã Châu village, Vietnam

The history of industrial silk in the Usa is largely tied to several smaller urban centers in the Northeast region. Beginning in the 1830s, Manchester, Connecticut emerged as the early center of the silk industry in America, when the Cheney Brothers became the offset in the Usa to properly heighten silkworms on an industrial scale; today the Cheney Brothers Historic Commune showcases their old mills.[52] With the mulberry tree craze of that decade, other smaller producers began raising silkworms. This economic system particularly gained traction in the vicinity of Northampton, Massachusetts and its neighboring Williamsburg, where a number of small firms and cooperatives emerged. Among the most prominent of these was the cooperative utopian Northampton Association for Education and Industry, of which Sojourner Truth was a fellow member.[53] Post-obit the destructive Mill River Overflowing of 1874, one manufacturer, William Skinner, relocated his factory from Williamsburg to the then-new city of Holyoke. Over the next 50 years he and his sons would maintain relations between the American silk manufacture and its counterparts in Japan,[54] and expanded their business organisation to the point that by 1911, the Skinner Mill complex contained the largest silk mill under one roof in the globe, and the brand Skinner Fabrics had become the largest manufacturer of silk satins internationally.[51] [55] Other efforts later in the 19th century would likewise bring the new silk manufacture to Paterson, New Jersey, with several firms hiring European-born textile workers and granting it the nickname "Silk City" as another major centre of production in the United States.

World State of war II interrupted the silk merchandise from Asia, and silk prices increased dramatically.[56] U.S. industry began to wait for substitutes, which led to the utilise of synthetics such as nylon. Synthetic silks have also been made from lyocell, a type of cellulose fiber, and are often hard to distinguish from real silk (see spider silk for more on synthetic silks).

Malaysia

In Terengganu, which is at present part of Malaysia, a second generation of silkworm was existence imported every bit early equally 1764 for the country'due south silk cloth industry, particularly songket.[57] Still, since the 1980s, Malaysia is no longer engaged in sericulture but does plant mulberry copse.

Vietnam

In Vietnamese legend, silk appeared in the commencement millennium Advertising and is however being woven today.

Production procedure

The procedure of silk production is known every bit sericulture.[58] The unabridged production process of silk can be divided into several steps which are typically handled by different entities.[ clarification needed ] Extracting raw silk starts by cultivating the silkworms on mulberry leaves. In one case the worms showtime pupating in their cocoons, these are dissolved in boiling water in order for individual long fibres to exist extracted and fed into the spinning reel.[59]

To produce one kg of silk, 104 kg of mulberry leaves must be eaten by 3000 silkworms. Information technology takes about 5000 silkworms to make a pure silk kimono.[60] : 104 The major silk producers are China (54%) and India (14%).[61] Other statistics:[62]

| Summit Ten Cocoons (Reelable) Producers – 2005 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (Int $k) | Footnote | Production (1000 kg) | Footnote |

| | 978,013 | C | 290,003 | F |

| | 259,679 | C | 77,000 | F |

| | 57,332 | C | 17,000 | F |

| | 37,097 | C | 11,000 | F |

| | twenty,235 | C | half dozen,088 | F |

| | sixteen,862 | C | 5,000 | F |

| | 10,117 | C | 3,000 | F |

| | five,059 | C | one,500 | F |

| | 3,372 | C | 1,000 | F |

| | 2,023 | C | 600 | F |

| No symbol = official figure, F = FAO approximate,*= Unofficial figure, C = Calculated figure; Production in Int $1000 have been calculated based on 1999–2001 international prices | ||||

The environmental impact of silk production is potentially large when compared with other natural fibers. A life-wheel assessment of Indian silk production shows that the product process has a big carbon and water footprint, mainly due to the fact that it is an animal-derived fiber and more than inputs such as fertilizer and water are needed per unit of cobweb produced.[63]

Properties

Models in silk dresses at the MoMo Falana fashion show

Physical properties

Silk fibers from the Bombyx mori silkworm have a triangular cantankerous section with rounded corners, 5–10 μm wide. The fibroin-heavy chain is composed mostly of beta-sheets, due to a 59-mer amino acid repeat sequence with some variations.[64] The apartment surfaces of the fibrils reverberate calorie-free at many angles, giving silk a natural sheen. The cross-section from other silkworms can vary in shape and bore: crescent-like for Anaphe and elongated wedge for tussah. Silkworm fibers are naturally extruded from 2 silkworm glands equally a pair of primary filaments (brin), which are stuck together, with sericin proteins that deed like glue, to course a bave. Bave diameters for tussah silk can reach 65 μm. See cited reference for cross-sectional SEM photographs.[65]

Raw silk of domesticated silk worms, showing its natural smoothen.

Silk has a smooth, soft texture that is not slippery, unlike many synthetic fibers.

Silk is one of the strongest natural fibers, but information technology loses upwards to xx% of its strength when moisture. Information technology has a good moisture regain of 11%. Its elasticity is moderate to poor: if elongated even a small amount, it remains stretched. It can exist weakened if exposed to too much sunlight. It may also be attacked by insects, specially if left muddy.

Ane case of the durable nature of silk over other fabrics is demonstrated by the recovery in 1840 of silk garments from a wreck of 1782: 'The near durable article found has been silk; for as well pieces of cloaks and lace, a pair of blackness satin breeches, and a big satin waistcoat with flaps, were got up, of which the silk was perfect, but the lining entirely gone ... from the thread giving way ... No articles of dress of woollen fabric have still been found.'[66]

Silk is a poor conductor of electricity and thus susceptible to static cling. Silk has a high emissivity for infrared light, making information technology feel absurd to the bear upon.[67]

Unwashed silk chiffon may shrink up to 8% due to a relaxation of the fiber macrostructure, so silk should either be washed prior to garment structure, or dry cleaned. Dry cleaning may notwithstanding compress the chiffon up to 4%. Occasionally, this shrinkage can be reversed past a gentle steaming with a press material. There is most no gradual shrinkage nor shrinkage due to molecular-level deformation.

Natural and synthetic silk is known to manifest piezoelectric backdrop in proteins, probably due to its molecular structure.[68]

Silkworm silk was used as the standard for the denier, a measurement of linear density in fibers. Silkworm silk therefore has a linear density of approximately 1 den, or ane.1 dtex.

| Comparison of silk fibers[69] | Linear density (dtex) | Diameter (μm) | Coeff. variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moth: Bombyx mori | i.17 | 12.ix | 24.8% |

| Spider: Argiope aurantia | 0.xiv | 3.57 | 14.8% |

Chemical properties

Silk emitted by the silkworm consists of two main proteins, sericin and fibroin, fibroin being the structural center of the silk, and serecin being the sticky material surrounding information technology. Fibroin is made up of the amino acids Gly-Ser-Gly-Ala-Gly-Ala and forms beta pleated sheets. Hydrogen bonds form betwixt chains, and side chains form above and below the plane of the hydrogen bond network.

The high proportion (50%) of glycine allows tight packing. This is because glycine's R group is only a hydrogen and so is not every bit sterically constrained. The addition of alanine and serine makes the fibres strong and resistant to breaking. This tensile strength is due to the many interceded hydrogen bonds, and when stretched the force is practical to these numerous bonds and they do non break.

Silk resists near mineral acids, except for sulfuric acid, which dissolves it. It is yellowed by perspiration. Chlorine bleach will as well destroy silk fabrics.

Variants

Regenerated silk fiber

RSF is produced by chemically dissolving silkworm cocoons, leaving their molecular structure intact. The silk fibers dissolve into tiny thread-like structures known as microfibrils. The resulting solution is extruded through a small opening, causing the microfibrils to reassemble into a single cobweb. The resulting fabric is reportedly twice as potent equally silk.[70]

Applications

Vesture

Silk'due south absorbency makes it comfortable to vesture in warm weather and while agile. Its depression conductivity keeps warm air close to the pare during cold weather. Information technology is often used for clothing such every bit shirts, ties, blouses, formal dresses, high-fashion clothes, lining, lingerie, pajamas, robes, dress suits, sun dresses, and Eastern folk costumes. For practical utilize, silk is excellent as vesture that protects from many bitter insects that would commonly pierce clothing, such as mosquitoes and horseflies.

Fabrics that are often made from silk include charmeuse, habutai, chiffon, taffeta, crêpe de chine, dupioni, noil, tussah, and shantung, among others.

Furniture

Silk's attractive lustre and drape makes it suitable for many furnishing applications. Information technology is used for upholstery, wall coverings, window treatments (if blended with some other fiber), rugs, bedding, and wall hangings.[71]

Manufacture

Silk had many industrial and commercial uses, such as in parachutes, bicycle tires, comforter filling, and arms gunpowder bags.[72]

Medicine

A special manufacturing process removes the outer sericin coating of the silk, which makes it suitable as non-absorbable surgical sutures. This process has also recently led to the introduction of specialist silk underclothing, which has been used for peel conditions including eczema.[73] [74] New uses and manufacturing techniques have been institute for silk for making everything from disposable cups to drug commitment systems and holograms.[75]

Biomaterial

Silk began to serve every bit a biomedical material for sutures in surgeries as early on as the second century CE.[76] In the by 30 years, information technology has been widely studied and used as a biomaterial due to its mechanical strength, biocompatibility, tunable degradation charge per unit, ease to load cellular growth factors (for example, BMP-two), and its ability to be processed into several other formats such as films, gels, particles, and scaffolds.[77] Silks from Bombyx mori, a kind of cultivated silkworm, are the most widely investigated silks.[78]

Silks derived from Bombyx mori are mostly made of 2 parts: the silk fibroin cobweb which contains a light chain of 25kDa and a heavy concatenation of 350kDa (or 390kDa[79]) linked by a single disulfide bond[fourscore] and a glue-like poly peptide, sericin, comprising 25 to 30 percentage past weight. Silk fibroin contains hydrophobic beta canvass blocks, interrupted by small-scale hydrophilic groups. And the beta-sheets contribute much to the high mechanical strength of silk fibers, which achieves 740 MPa, tens of times that of poly(lactic acrid) and hundreds of times that of collagen. This impressive mechanical strength has fabricated silk fibroin very competitive for applications in biomaterials. Indeed, silk fibers take found their fashion into tendon tissue engineering,[81] where mechanical properties affair greatly. In improver, mechanical backdrop of silks from diverse kinds of silkworms vary widely, which provides more choices for their use in tissue engineering.

About products made from regenerated silk are weak and brittle, with just ≈one–2% of the mechanical strength of native silk fibers due to the absenteeism of appropriate secondary and hierarchical construction,

| Source Organisms[82] | Tensile strength (g/den) | Tensile modulus (g/den) | Breaking strain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bombyx mori | 4.iii–v.two | 84–121 | 10.0–23.4 |

| Antheraea mylitta | 2.v–4.5 | 66–70 | 26–39 |

| Philosamia cynthia ricini | 1.9–3.5 | 29–31 | 28.0–24.0 |

| Coscinocera hercules | five ± i | 87 ± 17 | 12 ± 5 |

| Hyalophora euryalus | 2.vii ± 0.9 | 59 ± eighteen | 11 ± 6 |

| Rothschildia hesperis | 3.three ± 0.eight | 71 ± 16 | x ± 4 |

| Eupackardia calleta | 2.viii ± 0.seven | 58 ± 18 | 12 ± vi |

| Rothschildia lebeau | iii.one ± 0.8 | 54 ± fourteen | 16 ± 7 |

| Antheraea oculea | iii.1 ± 0.8 | 57 ± 15 | 15 ± 7 |

| Hyalophora gloveri | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 48 ± xiii | 19 ± vii |

| Copaxa multifenestrata | 0.nine ± 0.2 | 39 ± vi | 4 ± iii |

Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility, i.e., to what level the silk will cause an immune response, is a critical issue for biomaterials. The issue arose during its increasing clinical utilize. Wax or silicone is ordinarily used equally a coating to avoid fraying and potential immune responses[77] when silk fibers serve as suture materials. Although the lack of detailed characterization of silk fibers, such as the extent of the removal of sericin, the surface chemic properties of coating material, and the process used, go far hard to determine the real immune response of silk fibers in literature, information technology is generally believed that sericin is the major crusade of immune response. Thus, the removal of sericin is an essential step to clinch biocompatibility in biomaterial applications of silk. However, further research fails to prove conspicuously the contribution of sericin to inflammatory responses based on isolated sericin and sericin based biomaterials.[83] In addition, silk fibroin exhibits an inflammatory response similar to that of tissue culture plastic in vitro[84] [85] when assessed with human being mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) or lower than collagen and PLA when implant rat MSCs with silk fibroin films in vivo.[85] Thus, appropriate degumming and sterilization will clinch the biocompatibility of silk fibroin, which is further validated by in vivo experiments on rats and pigs.[86] There are still concerns nigh the long-term safety of silk-based biomaterials in the homo body in dissimilarity to these promising results. Even though silk sutures serve well, they exist and interact within a limited menstruation depending on the recovery of wounds (several weeks), much shorter than that in tissue engineering. Another business arises from biodegradation because the biocompatibility of silk fibroin does not necessarily clinch the biocompatibility of the decomposed products. In fact, different levels of immune responses[87] [88] and diseases[89] take been triggered by the degraded products of silk fibroin.

Biodegradability

Biodegradability (also known as biodegradation)—the power to be disintegrated by biological approaches, including bacteria, fungi, and cells—is another significant property of biomaterials today. Biodegradable materials tin can minimize the pain of patients from surgeries, peculiarly in tissue technology, in that location is no need of surgery in order to remove the scaffold implanted. Wang et al.[90] showed the in vivo degradation of silk via aqueous 3-D scaffolds implanted into Lewis rats. Enzymes are the means used to achieve deposition of silk in vitro. Protease XIV from Streptomyces griseus and α-chymotrypsin from bovine pancreases are the two popular enzymes for silk deposition. In addition, gamma radiations, every bit well as cell metabolism, tin can also regulate the degradation of silk.

Compared with synthetic biomaterials such as polyglycolides and polylactides, silk is obviously advantageous in some aspects in biodegradation. The acidic degraded products of polyglycolides and polylactides will decrease the pH of the ambient surroundings and thus adversely influence the metabolism of cells, which is not an upshot for silk. In addition, silk materials can retain forcefulness over a desired flow from weeks to months equally needed by mediating the content of beta sheets.

Genetic modification

Genetic modification of domesticated silkworms has been used to alter the composition of the silk.[91] Too as possibly facilitating the production of more than useful types of silk, this may allow other industrially or therapeutically useful proteins to be made by silkworms.[92]

Cultivation

Silk moths lay eggs on particularly prepared paper. The eggs hatch and the caterpillars (silkworms) are fed fresh mulberry leaves. After about 35 days and 4 moltings, the caterpillars are 10,000 times heavier than when hatched and are ready to begin spinning a cocoon. A harbinger frame is placed over the tray of caterpillars, and each caterpillar begins spinning a cocoon by moving its head in a design. Two glands produce liquid silk and forcefulness it through openings in the caput called spinnerets. Liquid silk is coated in sericin, a water-soluble protective gum, and solidifies on contact with the air. Within 2–three days, the caterpillar spins about 1 mile of filament and is completely encased in a cocoon. The silk farmers then oestrus the cocoons to kill them, leaving some to metamorphose into moths to breed the adjacent generation of caterpillars. Harvested cocoons are then soaked in boiling water to soften the sericin holding the silk fibers together in a cocoon shape. The fibers are and so unwound to produce a continuous thread. Since a single thread is also fine and fragile for commercial use, anywhere from three to 10 strands are spun together to form a single thread of silk.[93]

Animal rights

As the process of harvesting the silk from the cocoon kills the larvae by boiling them, sericulture has been criticized by animal welfare and rights activists.[94]

Mahatma Gandhi was critical of silk production based on the Ahimsa philosophy, which led to the promotion of cotton and Ahimsa silk, a blazon of wild silk made from the cocoons of wild and semi-wild silk moths.[95]

Since silk cultivation kills silkworms, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) urges people not to buy silk items.[96]

See also

- Art silk

- Bulletproofing

- International Yr of Natural Fibres

- Mommes

- Rayon

- Sea silk

- Silk waste

- Sinchaw

- Spider silk

References

Citations

- ^ "Silk". The Free Dictionary By Farlex. Archived from the original on three July 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ a b Sutherland TD, Young JH, Weisman S, Hayashi CY, Merritt DJ (2010). "Insect silk: one name, many materials". Annual Review of Entomology. 55: 171–88. doi:ten.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085401. PMID 19728833.

- ^ Walker AA, Weisman S, Church JS, Merritt DJ, Mudie ST, Sutherland TD (2012). "Silk from Crickets: A New Twist on Spinning". PLOS One. seven (2): e30408. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...730408W. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0030408. PMC3280245. PMID 22355311.

- ^ "Silk". Etymonline. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 27 Baronial 2012.

- ^ Sindya N. Bhanoo (xx May 2011). "Silk Production Takes a Walk on the Wild Side". New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ "Chance coming together leads to creation of antibiotic spider silk". phys.org. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "Cobweb Art a Triumph of Whimsy Over Practicality: Northwestern University News". world wide web.northwestern.edu. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved thirteen September 2019.

- ^ a b Hogue, Charles Leonard (1993). Latin American insects and entomology . Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 325. ISBN978-0520078499. OCLC 25164105.

Silk swaths gathered from the large hammock-net cocoons of Gloveria psidii (= Sagana sapotoza) and pasted together to form a kind of hard cloth, or paper, were an important trade item in Mexico at the time of Moctezuma II

- ^ Hill (2004). Appendix E.

- ^ Hill (2009). "Appendix C: Wild Silks," pp.477–480.

- ^ Gheysens, T; Collins, A; Raina, Southward; Vollrath, F; Knight, D (2011). "Demineralization enables reeling of Wild Silkmoth cocoons" (PDF). Biomacromolecules. 12 (6): 2257–66. doi:ten.1021/bm2003362. hdl:1854/LU-2153669. PMID 21491856. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Vainker, Shelagh (2004). Chinese Silk: A Cultural History. Rutgers University Press. pp. xx, 17. ISBN978-0813534466.

- ^ "Silk: History". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). Columbia University Press. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008.

- ^ "Oldest Bear witness of Silk Found in 8,500-Year-Old Tombs". Live Science. 10 Jan 2017. Archived from the original on 13 Oct 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "Prehistoric silk found in Henan". The Establish of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (IA CASS). Archived from the original on four January 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Cloth Exhibition: Introduction". Asian art. Archived from the original on 8 September 2007.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. p. xviii. ISBN978-1606060834.

- ^ a b "Chinese archaeologists brand ground-breaking textile discovery in ii,500-year-old tomb". People'southward Daily Online. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 26 Baronial 2007.

- ^ Lubec, Chiliad.; J. Holaubek; C. Feldl; B. Lubec; Due east. Strouhal (four March 1993). "Use of silk in ancient Egypt". Nature. 362 (6415): 25. Bibcode:1993Natur.362...25L. doi:10.1038/362025b0. S2CID 1001799. Archived from the original on 20 September 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)) - ^ Kundu, Subhas (24 March 2014). Silk Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Elsevier Science. pp. 3–. ISBN978-0-85709-706-four.

- ^ Hill (2009). Appendix A: "Introduction of Silk Cultivation to Khotan in the 1st Century CE," pp. 466–467.

- ^ "History of Sericulture" (PDF). Government of Andhra Pradesh (Bharat) – Department of Sericulture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Garthwaite, Gene Ralph (2005). The Persians. Oxford & Carlton: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd. p. 78. ISBN978-1-55786-860-2.

- ^ a b Ball, Philip (17 February 2009). "Rethinking silk's origins". Nature. 457 (7232): 945. doi:10.1038/457945a. PMID 19238684. S2CID 4390646.

- ^ Good, I.L.; Kenoyer, J.Thousand.; Meadow, R.H. (2009). "New bear witness for early on silk in the Indus civilization" (PDF). Archaeometry. fifty (3): 457. doi:ten.1111/j.1475-4754.2008.00454.10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Tn Sericulture Archived 19 Baronial 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Tn Sericulture (30 June 2014).

- ^ "Silk city to come almost B'lore". Deccan Herald. 17 Oct 2009. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu News: Tamil Nadu's first automatic silk reeling unit opened". The Hindu. 24 August 2008. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Nigh Thai silk Archived 9 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine from World of Thai Silk (commercial)

- ^ Silk – Banglapedia Archived iv March 2016 at the Wayback Car. En.banglapedia.org (10 March 2015). Retrieved on 2016-08-02.

- ^ a b Whitfield, Susan (2004). The Silk Route: Merchandise, Travel, War and Religion. British Library. Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 110. ISBN978-i-932476-thirteen-2. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "Silk: Why Information technology Is Haram for Men". 23 September 2003. Archived from the original on two March 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ^ Odyssey 19 233–234: τὸν δὲ χιτῶν' ἐνόησα περὶ χροῒ σιγαλόεντα, οἷόν τε κρομύοιο λοπὸν κάτα ἰσχαλέοιο· = "And I [= Odysseus

- ^ Tacitus (1989). Annals. ISBN978-0-521-31543-2. Archived from the original on thirty June 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Historia Augusta Vita Heliogabali. Book 26.1.

- ^ Procopius (1928). History of the Wars. Book viii.17. ISBN978-0-674-992399.

- ^ "Italy – Calabria, Catanzaro". Office of Tourism. Archived from the original on 21 Baronial 2015.

- ^ Postrel, Virginia (2020). The Fabric of Civilization. New York: Basic Books. pp. 55–59. ISBN9781541617629.

- ^ "La Lonja de la Seda de Valencia". UNESCO Earth Heritage Centre. Whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved x April 2011.

- ^ Diccionari Aguiló: materials lexicogràfics / aplegats per Marià Aguiló i Fuster; revisats i publicats sota la cura de Pompeu Fabra i Manuel de Montoliu, page 134, Institut d'Estudis Catalans, Barcelona 1929.

- ^ Delgado, José Luis (8 October 2012) "La seda de Granada era la mejor" Archived 26 Baronial 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Granada Hoy

- ^ Intxausti, Aurora (ane May 2013) "La Alpujarra poseía four.000 telares de seda antes de la expulsión de los moriscos" Archived 26 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, El País.

- ^ Callandine 1993

- ^ "Lullingstone Silk Farm". world wide web.lullingstonecastle.co.uk. Archived from the original on ten January 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ BOND, Barbara A (2014). "MI9'due south escape and evasion mapping plan 1939-1945" (PDF). Academy of Plymouth. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ Nash, Eric P. (30 July 1995). "STYLE; Dressed to Impale". The New York Times. Archived from the original on nine November 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ Huzjan, Vladimir (July 2008). "Pokušaj otkrivanja nastanka i razvoja kravate kao riječi i odjevnoga predmeta" [The origin and development of the tie (kravata) as a word and equally a garment]. Povijesni Prilozi (in Croatian). 34 (34): 103–120. ISSN 0351-9767. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Silk Product in Konavle". Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 22 Apr 2015.

- ^ P.K., Kevan; R.A., Bye (1991). "natural history, sociobiology, and ethnobiology of Eucheira socialis Westwood (Lepidoptera: Pieridae), a unique and petty-known butterfly from Mexico". Entomologist. ISSN 0013-8878. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ de Avila, Alejandro (1997). Klein, Kathryn (ed.). The Unbroken Thread: Conserving the Textile Traditions of Oaxaca (PDF). Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute. pp. 125–126. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ a b "The Largest Silk Manufactory in the World; The Story of Skinner Silks and Satins". Silk. Vol. 5, no. 6. New York: Silk Publishing Visitor. May 1912. pp. 62–64. Archived from the original on 29 Jan 2020. Retrieved 14 Dec 2018.

- ^ "Cheney Brothers Historic District". National Historic Landmark summary list. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ Owens, Jody (12 April 2002). "Becoming Sojourner Truth: The Northampton Years". Silk in Northampton. Smith College. Archived from the original on 17 Baronial 2003.

- ^ For give-and-take on W. Skinner 2's relations with Japanese ministers and merchant-traders, come across Lindsay Russell, ed. (1915). America to Japan: A Symposium of Papers by Representative Citizens of the United states on the Relations between Japan and America and on the Mutual Interests of the Two Countries. New York: G.P. Putnam'southward Sons; The Knickerbocker Press; The Nippon Club. p. 66. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

-

- "Tiffin to Commissioner Shito". The American Silk Periodical. Silk Association of America. XXXIV: 32. May 1915. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Reischauer, Haru Matsukata (1986). "Starting the Silk Merchandise". Samurai and Silk: A Japanese and American Heritage. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 207–209. ISBN9780674788015. Archived from the original on thirty December 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

-

- ^ Thibodeau, Kate Navarra (viii June 2009). "William Skinner & Holyoke's Water Power". Valley Advocate. Northampton, Mass. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved fourteen Dec 2018.

- ^ Weatherford, D (2009). American Women During Globe War 2: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 97. ISBN978-0415994750.

- ^ Mohamad, Maznah (1996). The Malayhandloom weavers:a report of the rise and refuse of traditional. ISBN9789813016996 . Retrieved ix November 2013.

- ^ Pedigo, Larry P.; Rice, Marlin E. (2014). Entomology and Pest Management: 6th Edition. Waveland Press. ISBN978-1478627708.

- ^ Bezzina, Neville. "Silk Production Process". senature.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012.

- ^ Fritz, Anne and Cant, Jennifer (1986). Consumer Textiles. Oxford University Press Commonwealth of australia. Reprint 1987. ISBN 0-19-554647-four.

- ^ "Mulberry Silk – Fabric Fibres – Handloom Textiles | Handwoven Fabrics | Natural Fabrics | Cotton dress in Chennai". Brasstacksmadras.com. Archived from the original on 9 Nov 2013. Retrieved 9 Nov 2013.

- ^ "Statistics". inserco.org. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016.

- ^ Astudillo, Miguel F.; Thalwitz, Gunnar; Vollrath, Fritz (October 2014). "Life cycle assessment of Indian silk". Journal of Cleaner Production. 81: 158–167. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.06.007.

- ^ "Handbook of Fiber Chemistry", Menachem Lewin, Editor, third ed., 2006, CRC press, ISBN 0-8247-2565-4

- ^ "Handbook of Cobweb Chemistry", Menachem Lewin, Editor, 2d ed.,1998, Marcel Dekker, pp. 438–441, ISBN 0-8247-9471-0

- ^ The Times, London, article CS117993292, 12 October 1840.

- ^ Venere, Emil (31 January 2018). "Silk fibers could be high-tech 'natural metamaterials'". Phys.org. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ "Piezoelectricity in Natural and Constructed Silks" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on twenty July 2011. Retrieved 28 Apr 2010.

- ^ Ko, Frank K.; Kawabata, Sueo; Inoue, Mari; Niwa, Masako. "Technology Properties of Spider Silk" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "To most match spider silk, scientists regenerate silkworm silk". newatlas.com. ten Nov 2017. Archived from the original on x November 2017. Retrieved 18 Dec 2017.

- ^ Murthy, H. V. Sreenivasa (2018). Introduction to Fabric Fibres. WPI Republic of india. ISBN9781315359335.

- ^ "Silk Pulverisation or Cartridge Bag Cloth". americanhistory.si.edu. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved xxx May 2017.

- ^ Ricci, Yard.; Patrizi, A.; Bendandi, B.; Menna, G.; Varotti, E.; Masi, One thousand. (2004). "Clinical effectiveness of a silk fabric in the treatment of atopic dermatitis". The British Journal of Dermatology. 150 (i): 127–131. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05705.x. PMID 14746626. S2CID 31408225.

- ^ Senti, Grand.; Steinmann, L. S.; Fischer, B.; Kurmann, R.; Storni, T.; Johansen, P.; Schmid-Grendelmeier, P.; Wuthrich, B.; Kundig, T. M. (2006). "Antimicrobial silk clothing in the handling of atopic dermatitis proves comparable to topical corticosteroid treatment". Dermatology. 213 (3): 228–233. doi:10.1159/000095041. PMID 17033173. S2CID 21648775.

- ^ Omenetto, Fiorenzo. "Silk, the ancient material of the future – Talk Video – TED.com". ted.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014.

- ^ Muffly, Tyler; Tizzano, Anthony; Walters, Marker (March 2011). "The history and evolution of sutures in pelvic surgery". Periodical of the Royal Society of Medicine. 104 (three): 107–12. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2010.100243. PMC3046193. PMID 21357979.

Galen also recommended using silk suture when available.

- ^ a b Rockwood, Danielle N; Preda, Rucsanda C; Yücel, Tuna; Wang, Xiaoqin; Lovett, Michael Fifty; Kaplan, David Fifty (2011). "Materials fabrication from Bombyx mori silk fibroin". Nature Protocols. 6 (10): 1612–1631. doi:10.1038/nprot.2011.379. PMC3808976. PMID 21959241.

- ^ Altman, Gregory H; Diaz, Frank; Jakuba, Caroline; Calabro, Tara; Horan, Rebecca L; Chen, Jingsong; Lu, Helen; Richmond, John; Kaplan, David Fifty (1 February 2003). "Silk-based biomaterials". Biomaterials. 24 (iii): 401–416. CiteSeerXten.1.1.625.3644. doi:x.1016/S0142-9612(02)00353-8. PMID 12423595.

- ^ Vepari, Charu; Kaplan, David L. (ane Baronial 2007). "Silk equally a biomaterial". Progress in Polymer Science. Polymers in Biomedical Applications. 32 (viii–nine): 991–1007. doi:ten.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.013. PMC2699289. PMID 19543442.

- ^ Zhou, Cong-Zhao; Confalonieri, Fabrice; Medina, Nadine; Zivanovic, Yvan; Esnault, Catherine; Yang, Necktie; Jacquet, Michel; Janin, Joel; Duguet, Michel (15 June 2000). "Fine arrangement of Bombyx mori fibroin heavy concatenation gene". Nucleic Acids Research. 28 (12): 2413–2419. doi:10.1093/nar/28.12.2413. PMC102737. PMID 10871375.

- ^ Kardestuncer, T; McCarthy, M B; Karageorgiou, 5; Kaplan, D; Gronowicz, Yard (2006). "RGD-tethered Silk Substrate Stimulates the Differentiation of Human Tendon Cells". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 448: 234–239. doi:x.1097/01.blo.0000205879.50834.fe. PMID 16826121. S2CID 23123.

- ^ Kundu, Banani; Rajkhowa, Rangam; Kundu, Subhas C.; Wang, Xungai (1 Apr 2013). "Silk fibroin biomaterials for tissue regenerations". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. Bionics – Biologically inspired smart materials. 65 (four): 457–470. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.043. PMID 23137786.

- ^ Zhang, Yaopeng; Yang, Hongxia; Shao, Huili; Hu, Xuechao (5 May 2010). "Antheraea pernyiSilk Cobweb: A Potential Resources for Artificially Biospinning Spider Dragline Silk". Periodical of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2010: 683962. doi:x.1155/2010/683962. PMC2864894. PMID 20454537.

- ^ Wray, Lindsay S.; Hu, Xiao; Gallego, Jabier; Georgakoudi, Irene; Omenetto, Fiorenzo G.; Schmidt, Daniel; Kaplan, David 50. (1 October 2011). "Effect of processing on silk-based biomaterials: Reproducibility and biocompatibility". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 99B (1): 89–101. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.31875. PMC3418605. PMID 21695778.

- ^ a b Meinel, Lorenz; Hofmann, Sandra; Karageorgiou, Vassilis; Kirker-Caput, Carl; McCool, John; Gronowicz, Gloria; Zichner, Ludwig; Langer, Robert; Vunjak-Novakovic, Gordana (ane January 2005). "The inflammatory responses to silk films in vitro and in vivo". Biomaterials. 26 (2): 147–155. doi:x.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.047. PMID 15207461.

- ^ Fan, Hongbin; Liu, Haifeng; Toh, Siew 50.; Goh, James C.H. (2009). "Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and silk scaffold in large creature model". Biomaterials. xxx (28): 4967–4977. doi:ten.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.048. PMID 19539988.

- ^ Minoura, Northward.; Aiba, Due south.; Higuchi, M.; Gotoh, Y.; Tsukada, Yard.; Imai, Y. (17 March 1995). "Zipper and growth of fibroblast cells on silk fibroin". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 208 (ii): 511–516. doi:ten.1006/bbrc.1995.1368. PMID 7695601.

- ^ Gellynck, Kris; Verdonk, Peter C. M.; Van Nimmen, Els; Almqvist, Karl F.; Gheysens, Tom; Schoukens, Gustaaf; Van Langenhove, Lieva; Kiekens, Paul; Mertens, Johan (i November 2008). "Silkworm and spider silk scaffolds for chondrocyte back up". Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 19 (eleven): 3399–3409. doi:10.1007/s10856-008-3474-6. PMID 18545943. S2CID 27191387.

- ^ Lundmark, Katarzyna; Westermark, Gunilla T.; Olsén, Arne; Westermark, Per (26 April 2005). "Protein fibrils in nature can raise amyloid poly peptide A amyloidosis in mice: Cross-seeding as a disease mechanism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the The states of America. 102 (17): 6098–6102. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.6098L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501814102. PMC1087940. PMID 15829582.

- ^ Wang, Yongzhong; Rudym, Darya D.; Walsh, Ashley; Abrahamsen, Lauren; Kim, Hyeon-Joo; Kim, Hyun Southward.; Kirker-Head, Carl; Kaplan, David L. (2008). "In vivo deposition of three-dimensional silk fibroin scaffolds". Biomaterials. 29 (24–25): 3415–3428. doi:ten.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.002. PMC3206261. PMID 18502501.

- ^ Kojima, Thousand.; Kuwana, Y.; Sezutsu, H.; Kobayashi, I.; Uchino, K.; Tamura, T.; Tamada, Y. (2007). "A new method for the modification of fibroin heavy chain poly peptide in the transgenic silkworm". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 71 (12): 2943–2951. doi:ten.1271/bbb.70353. PMID 18071257. S2CID 44520735.

- ^ Tomita, Masahiro (April 2011). "Transgenic silkworms that weave recombinant proteins into silk cocoons". Biotechnology Letters. 33 (4): 645–654. doi:10.1007/s10529-010-0498-z. ISSN 1573-6776. PMID 21184136. S2CID 25310446.

- ^ Gleason, Carrie (2006) The Biography of Silk. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 12. ISBN 0778724875.

- ^ Stancati, Margherita (four January 2011). "Taking the Violence Out of Silk". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ Alexander, Horace Gundry; Centenary, National Committee for the Gandhi (1968). Mahatma Gandhi: 100 years. Gandhi Peace Foundation; Orient Longmans.

- ^ "Downward and Silk: Birds and Insects Exploited for Feathers and Textile". PETA. 19 March 2004. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 23 Jan 2014.

Silk Product Causes Painful Death for Insects

Bibliography

- Callandine, Anthony (1993). "Lombe's Mill: An Exercise in reconstruction". Industrial Archeology Review. XVI (one). ISSN 0309-0728.

- Hill, John E. (2004). The Peoples of the Westward from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Tertiary Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 Advertising. Draft annotated English translation. Appendix E.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Report of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to second centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-one-4392-2134-1.

- Magie, David (1924). Historia Augusta Life of Heliogabalus. Loeb Classical Texts No. 140: Harvard University Printing.ISBN 978-0674991552.

Further reading

- Feltwell, John (1990). The Story of Silk. Alan Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-86299-611-2.

- Proficient, Irene (Dec 1995). "On the question of silk in pre-Han Eurasia". Antiquity. Vol. 69, Number 266. pp. 959–968.

- Kuhn, Dieter (1995). "Silk Weaving in Ancient People's republic of china: From Geometric Figures to Patterns of Pictorial Likeness." Chinese Science. 12. pp. 77–114.

- Liu, Xinru (1996). Silk and Faith: An Exploration of Fabric Life and the Thought of People, Advertizing 600–1200. Oxford University Press.

- Liu, Xinru (2010). The Silk Route in World History. Oxford Academy Printing. ISBN 978-0-nineteen-516174-8; ISBN 978-0-19-533810-two (pbk).

- Rayner, Hollins (1903). Silk throwing and waste silk spinning. Scott, Greenwood, Van Nostrand. OL 7174062M.

- Sung, Ying-Hsing. 1637. Chinese Applied science in the Seventeenth Century – T'ien-kung K'ai-wu. Translated and annotated by E-tu Zen Sun and Shiou-chuan Sun. Pennsylvania Country University Press, 1966. Reprint: Dover, 1997. "Chapter 2. Wearable materials".

- Kadolph, Sara J. (2007). Textiles (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 76–81.

- Ricci, M.; et al. (2004). "Clinical Effectiveness of a Silk Fabric in the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis". British Journal of Dermatology. Issue 150. pp. 127–131.

External links

| | Await up silk in Wiktionary, the gratis lexicon. |

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silk. |

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Silk |

- References to silk past Roman and Byzantine writers

- A series of maps depicting the global merchandise in silk

- History of traditional silk in martial arts uniforms

- Raising silkworms in classrooms for educational purposes (with photos)

- New thread in cloth of insect silks|physorg.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silk

0 Response to "123 You Know Silk a G"

Post a Comment